Whether flash fiction, short story, novel, or screenplay, every work of fiction must contain the 5 C’s—without any one of them, a story fails to be a story at all.

Whether flash fiction, short story, novel, or screenplay, every work of fiction must contain the 5 C’s—without any one of them, a story fails to be a story at all.

Just as a building must utilize certain structural items–a solid foundation, walls, joists and support beams—so must each story incorporate the 5 C’s. Yes, they really are that important.

The 5 C’s are: Character, Conflict, Climax, Conclusion, and Change.

Before we discuss writing a story and the required 5 C’s, it’s wise, even mandatory, to define the term for our needs.

A definition of story from Merriam Webster online reads: an account of incidents or events; a statement regarding the facts pertinent to a situation in question.

Oxforddictionaries.com says, An account of imaginary or real people and events told for entertainment.

The above definitions pertain to all stories, including those spoken by people that don’t adhere to the needs of a written and printable (hence, saleable) story—think of a friend explaining a conversation with someone you both know.

Other dictionaries give equally bland definitions, which for the most part are of little use to what constitutes a story from a writer’s (or reader’s) perspective.

The definition needs to be more clearly defined, consistent, at times unyielding even though there are uncountable ways which a character’s journey can be portrayed.

For our purposes, the definition of story can be summed up like this:

A character must solve a problem, and after repeated conflicts (obstacles), the character either succeeds or fails to reach the goal (climax), and because of said conclusion (outcome), the character and/or situation are changed.

Some contend at least one C (usually Change) can be removed and still constitute a story. They point to James Bond novels where super spy 007 remains pretty much the same at the end of each novel. Although the change is not within his “person,” there is change—he defeats the bad guy and saves the world from destruction. Change always lurks nearby, at times subtle, at times not, but always present.

Perhaps the character succeeds in one aspect and fails in another. That is something you decide as the story matures.

Characters are People, too

First and foremost, a story is about a character or characters the reader emotionally relates to. Without a bond, there is no reason for the reader to continue.

The bond adheres when the reader can relate to the character in some way, and this is done by developing well-rounded “people” with flaws, personal backgrounds that makes them who they are, and therefore unique . . . just like you.

Conflict is Imminent

The catalyst forcing the reader forward is a problem of great magnitude. The dilemma can be internal or external (and preferably both, especially in a longer piece), but must be important to the character—your lead MUST address the problem, and there is no way to avoid it. Otherwise, there is no story.

Character plus Conflicts Equals Climax

The character is beset by great adversity that threatens him/her and shatters their world. It must be of extreme importance to your lead (physical or emotional death, total ruin as in losing a loved one or one’s job/profession) and the character must overcome several conflicts to reach (or not reach) the goal you set forth. One hurdle is not enough, and they cannot be small, easily rectified problems.

Think of Jonathan who needs money for an operation to save his life. If Jonathan possesses something he can sell to pay for the life-saving operation (even if it hurts to part with the item), the selling is not enough to keep the reader’s interest. Instead, have Jonathan homeless and penniless. Nothing defines adversity like certain death.

Conclusion with a Future

Stories end.

The details at the beginning and the ensuing conflicts need to culminate to a satisfying conclusion.

Following several attempts to solve the problem (ideally, each increasingly more difficult than the one before), the character succeeds or fails, depending on the point of the story. Not all stories have happy endings where lovers embrace against the background of the sun disappearing on the horizon. Like life, people fail, but there is often also a silver lining.

Evident Change

A character is different at the conclusion of a story, and ideally changed by the challenges the writer puts forth. The change can be large or small, but like the goal, must be important. Perhaps the character learns a great lesson, sees the world and others in a new way, or simply resigns that their life-view is correct.

Let’s say Jonathan is depicted as a selfish man. While he’s desperately seeking treatment he meets a young boy who needs a transplant to save his life. Will Jonathan remain selfish, die alone in some alley, or will he go to great lengths to donate his organ to the boy and finally give his life meaning?

Whatever the realization, the character or their situation changes—the job offered, the girl won (or lost), and the conclusion illustrates the change, and thereby, points toward a future not told by the writer.

Put the character into a terrible predicament that gets increasingly worse, have them fight through the conflicts with courage or guile, finally reaching the resolution, for good or ill. By using the 5 C’s, you will hook the reader and pull them into and through your tale all the way to the end.

See you on the next page,

Rick “C” Langford

If you enjoyed this article, Sign up to follow Knights of Writ — Fiction Musings, and receive all future posts in your email. SHARE with fellow writers, and as always, comments are encouraged and highly appreciated. I respond to all blog comments: dialog between writers is crucial in the continuing effort of sharpening our skills.

I read a book today, oh boy

I read a book today, oh boy My last post

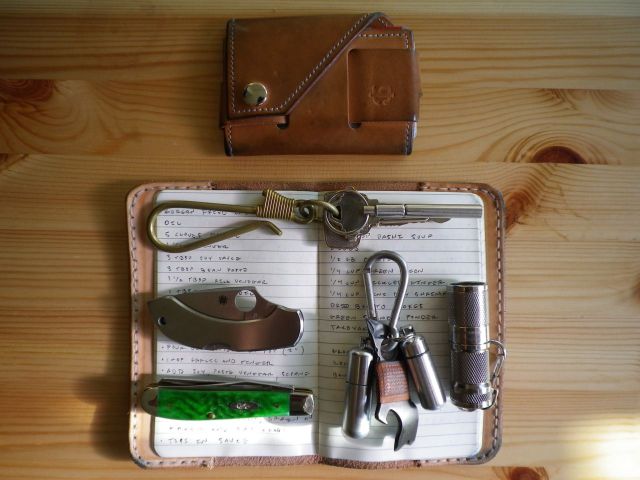

My last post Writing a novel entails dozens of scenes, locations, many characters—both vital and secondary—and the interactions between them, along with nuances, innuendos, hints, and foreshadowing to keep the reader enticed and turning the pages. Keeping track of all the finer points can be daunting, and the last thing you want as creator is to confuse the reader, or be unsure yourself.

Writing a novel entails dozens of scenes, locations, many characters—both vital and secondary—and the interactions between them, along with nuances, innuendos, hints, and foreshadowing to keep the reader enticed and turning the pages. Keeping track of all the finer points can be daunting, and the last thing you want as creator is to confuse the reader, or be unsure yourself. (1st 10 minutes of opening)

(1st 10 minutes of opening) My most recent post,

My most recent post,  In a previous post,

In a previous post,  Before computers and the internet, a writer’s life differed greatly: we typed our stories on a typewriter, made the necessary “editorial/proofreading” marks to correct mistakes and typos on the manuscript, and once satisfied the document was properly formatted—on 8 ½ x 11″ 20 lb. non-glossy paper, doubled spaced—packaged it in an envelope addressed to the correct editor for the specific publication.

Before computers and the internet, a writer’s life differed greatly: we typed our stories on a typewriter, made the necessary “editorial/proofreading” marks to correct mistakes and typos on the manuscript, and once satisfied the document was properly formatted—on 8 ½ x 11″ 20 lb. non-glossy paper, doubled spaced—packaged it in an envelope addressed to the correct editor for the specific publication. It happened one Sunday, Super Bowl Sunday to be exact. The day coincided with my mom’s birthday: she passed in 1999.

It happened one Sunday, Super Bowl Sunday to be exact. The day coincided with my mom’s birthday: she passed in 1999.